'Wear Your Love Like Heaven'

“Wear Your Love Like Heaven.” The single by British singer-songwriter Donovan reached number 23 on the Billboard pop chart in November 1967. What did it mean, you ask? Well, while the words were typically obscure for that artist and, especially, for that era, “wear your love like heaven” meant, essentially, “be nice” and “don’t be afraid to show it.”

My father, in his later years, used to say, “People just aren’t very nice anymore.” He died in 1989. Imagine how he’d feel about that now.

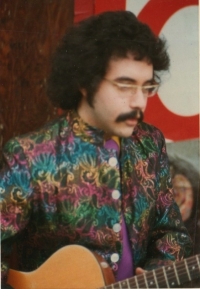

A couple of weeks before my father died, I met and talked to Donovan. I had arranged to meet him after a concert he gave in Cleveland, to interview him for a magazine article. Though he has never really stopped performing and writing songs (never for very long, anyway), his biggest successes came in the mid- to late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

When Donovan played that concert in Cleveland in the late ‘80s, it had been a long time since he’d performed here. When I arrived at the venue, I was shocked to see that about three-fourths of the audience members were dressed in full late-1960s hippie garb—possibly in clothes, glasses and belts, headbands and other accoutrements they still owned from that era, though I did overhear a couple of them say that they had scoured vintage clothing shops to find their outfits.

I thought it was completely stupid for them to wear that stuff to this concert, and kind of insulting to Donovan, too. And just to prove my point (to myself), when Donovan appeared onstage, he was wearing dress pants, an Izod shirt and loafers. Yay—I was right. Again.

Then, after the show, when Donovan and I sat alone in a small room, the first thing I said to him was, “Did you see all those people wearing hippie clothes?” And before I could follow that with what I really wanted to say—“Wasn’t that stupid?”—he said, “Yes. Wasn’t that nice of them?”

I took a breath and said, “Oh, uh . . . yes. Very nice.” And as I was sitting there lying to him, I was thinking: This guy is SO much nicer than I am.

In the 25-or-so intervening years, I’ve become much more tolerant and less judgmental. Or maybe that’s only in comparison to most of the rest of the world, which seems to have become less so. And I’m not talking about all the terrorists and warlords; I’m talking about regular people, like us (unless you’re a terrorist or a warlord), and the little things we do to other people.

I thought of my father’s words a few days ago, when I was in my car, trying to pull out of a side street into a larger thoroughfare. Car after car refused to stop to let me out, even when there would have been the space to do that, and even when they had a red light and couldn’t go anywhere, anyway. Finally, a nice woman stopped to let me out—until the man in the car behind her started BLASTING his horn and screaming at her to move up, thus rattling her and intimidating her enough that she quickly moved forward (so that HE could block me, while he waited for his red light to change).

And there was that woman at the Heinen’s at Green Road near Cedar one recent Sunday morning—a woman who refused to believe that she was being judgmental. I take my mother wherever she needs to go, including shopping, usually to that Heinen’s. When I had called my mother that morning, which I do every day, at least once a day, she mentioned some medication that she needed me to pick up, but which I had forgotten to make note of. When we got to the bananas, I suddenly remembered about the medicine. I took out my relatively smart phone, which I use, among other things, as a notepad, when I don’t have anything else to write with, and sent myself a very short message to pick up my mother’s prescription.

As I was doing that, a woman came over to us with her cart and asked me, “Is that your mother?” I said that she was, thinking that maybe the woman knew her, which often happens. But the woman pointed to my phone and said, “Well, I think that you should be talking to her, rather than doing that.”

So in two or three seconds of observation, she had the whole thing figured out: she knew that I was one of those people. I spent the next two or three minutes explaining to her—and, I admit, not very nicely—how many ways in which she was misguided in her assessment. In fact, I used that very word, assessment. Well . . . the first part of it, anyway. And I tried to point out to her how judgmental she had been. But, as you can probably imagine, she really didn’t want to hear it.

People rarely believe things like that about themselves. Like the many people in the Heights area who would never think of themselves as racist, and yet they talk and write on social media sites constantly about how much the Heights is “changing,” and, in their opinions, not for the better. But that’s a topic for another time.

In the meantime, I’ll try as hard as I can to wear my love like heaven. Until I run into that woman at Heinen’s again.

David Budin

David Budin is a freelance writer for national and local publications, the former editor of Cleveland Magazine and Northern Ohio Live, an author, and a professional musician and comedian. His writing focuses on the arts and, especially, pop-music history.